William Dunbar is a Scottish Makar. The Makars are 15th-16th century Scottish poets that wrote in Middle Scots during the reign of Scottish King James IV.

Middle Scots is, much like Middle English, a pain in the ass to read if you haven’t spent a lot of time with it, even more so if you haven’t even had any exposure to modern Scots. It is, however, worth it for the different, exciting, and intriguing ways language is used and life was thought about 5+ centuries ago.

Dunbar is one of the more famous Makars, at least as far as the Makars are famous. In an introduction to Dunbar’s works, John Conlee says he “may lay claim to being the finest lyric poet writing in English in the century and a half between the death of Chaucer in 1400 and the appearance of Tottel’s Miscellany in 1557.”

Dunbar is one of the more famous Makars, at least as far as the Makars are famous. In an introduction to Dunbar’s works, John Conlee says he “may lay claim to being the finest lyric poet writing in English in the century and a half between the death of Chaucer in 1400 and the appearance of Tottel’s Miscellany in 1557.”

Don’t take Conlee’s word for it, though. You can believe the Oxford Index, which states that Dunbar is one of the “most important poets of this group,” the other being Robert Henryson.

The Makars are also known as Scottish Chaucerians or Scot-Chaucerians, something that can be a sore spot among scholars for not acknowledging the originality of much of their work.

My exposure to William Dunbar has been through one of my professors, a medievalist that thought I would love to read Middle Scots after I enjoyed a class with her on Chaucer’s works. She was both right and wrong.

I enjoy reading the poems when I am in the mood and to calm my head when I get stressed about other things happening in life, like my job or athletics or you know, my actual classes.

However, the amount of time it takes to read Middle Scots almost always leaves me frustrated and craving modern English lines immediately below or next to every single Middle Scots one. They do make editions with interlinear translations (like this one), but my professor, being a serious academic with some serious standards and a knowledge of medieval languages, does not have one.

There are three poets in the book she gave me: Dunbar, Robert Henryson, and Gavin Douglas. After reading a sampling of each, I decided to stick with Dunbar.

I’ve had this book for almost two years and still haven’t finished all of his poems, but of the ones I have finished, I have a few favorite poems and lines that might just make you want to take some time out of your life to read a page or two of this man’s work.

They’ve made the time I’ve put into it worth it, and they make me a bit sad that I need to give her the book back since I’ll be leaving the country this time instead of the state.

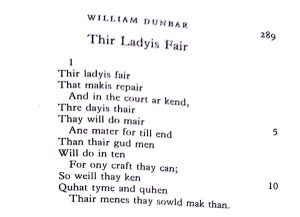

One of my favorites is “Thir Ladyis Fair,” which means “These Fair Ladies,” basically. I tried to find full translations of this, but my search proved futile, so I’ll have to give you some of my best amateur translations with some help from my professor’s book.

The opening stanza is as follows:

These fair ladies

That attend (the court)

And in the court are well known,

In three days there

They will do more

To conclude business

Than their husbands

Will do in ten

With any skill they possess;

So well they know

What time and when

They should make their cases.

I promise I don’t only like this poem because it talks about how awesome women are.

Dunbar shows extreme perceptiveness of the workings of the court, one that  questions the idea of women as decoration within his noble society. The poet is showing the role of women and even the ways they can be more skilled than their men, which is astute and commendable.

questions the idea of women as decoration within his noble society. The poet is showing the role of women and even the ways they can be more skilled than their men, which is astute and commendable.

It’s also impressive and satisfying how he managed to use his language and its grammatical structures to form the poem, something that doesn’t come across in my translation above but can be seen in the image of the first stanza from the book.

Some of my favorite lines come from “Now Lythis of ane Gentill Knycht” (Now Listen of a Noble Knight), translated as I understood them:

“ane full plum jurdane” – a foul fat chamber pot

“Robin under bewch” – Robin Hood. Mary, whose comment is below, pointed out that “bewch” is “bough or branch,” so I would translate this as “Robin under the branch(es).”

“Yet this far furth I dar him prais: / He fyld never sadell in his dais, / And Curry befyld twa” – “To this extent I dare to praise him: / He never dirtied his saddle in his life, / and Curry dirtied two.” (I’m pretty sure Dunbar isn’t talking about actual dirt here, if you get my drift.)

There’s a lot more information about Dunbar on the interwebs (just search “site:.edu William Dunbar Makar” and a lot will come up), and there are poems available online to read as well as some translations.

Your Bonnie Celtophile,

Dani

Scots is the language I have been studying. It would have been the language my great, great, great grandfather spoke. I enjoy reading your blog. Makes me feel as if I am touring Scotland. Slainte!

LikeLike

I’m glad to hear this. Slainte!

LikeLike

http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/beuch

bewch = bough or branch

LikeLike

Thanks! I’m going to update that.

LikeLike